General

Ease of Doing Business: Decriminalization of IP Laws

The provisions of the Jan Vishwas (Amendment of Provisions) Act, 2023 (“Act”) pertaining to Intellectual Property—Patents, Trademarks, Copyrights, and Geographical Indications (GI)—have come into force starting August 1, 2024, pursuant to the notification by the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT).

The Act amends certain provisions to decriminalise and rationalise offences to further enhance trust-based governance for ease of living and doing business. The Act was published in the Official Gazette on August 11, 2023.

However, the various provisions of the Act will come into force on the date the Central Government appoints by notification in the Official Gazette. Further, the Act provides that different dates may be appointed for amendments relating to different enactments.

Various provisions of the IP laws have either been amended or deleted to decriminalize certain offences and rationalize the various penalties. New Sections have been introduced which provide for a streamlined adjudicating mechanism for resolving disputes and imposing penalties, with provisions for appeals.

Additionally, for continuous accountability, the fines and penalties will progressively increase by ten per cent of the minimum amount after the expiry of every three years from the date of commencement of the Act.

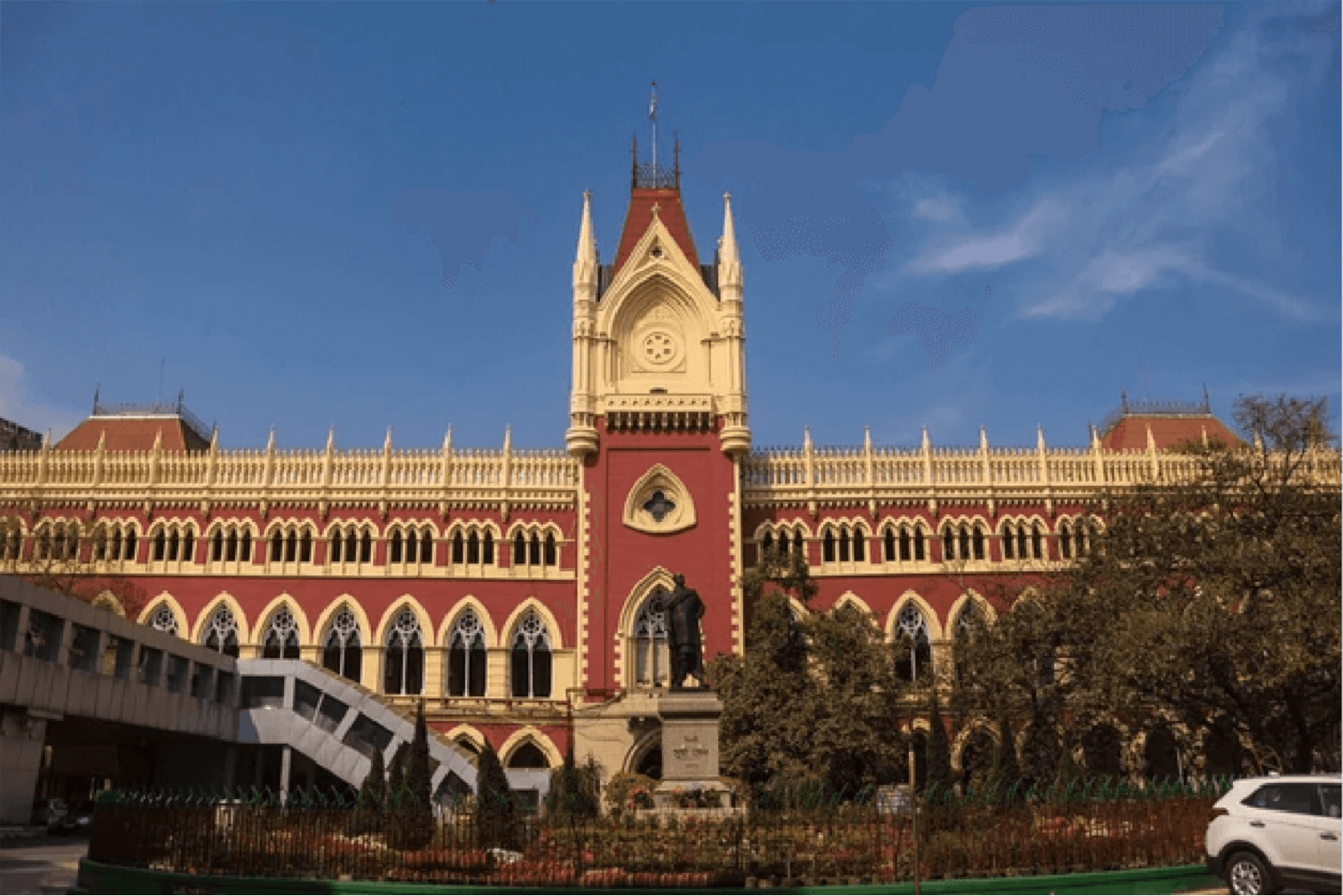

Calcutta High Court Joins the League: Becomes Third in India with Dedicated IP Division

The Calcutta High Court has become the third High Court in India, following the Delhi and Madras High Courts, to establish a dedicated Intellectual Property (IP) division. The notification regarding the Intellectual Property Rights Rules of the Calcutta High Court was published in the official gazette on September 20, 2024.

As per the rules, two divisions will be constituted: the Intellectual Property Rights Division (IPRD) and the Intellectual Property Rights Appellate Division (IPRAD). Judges for these divisions will be nominated by the Chief Justice of the High Court. Additionally, an Intellectual Property Rights Division Department will be set up to oversee the administration and management of the proceedings.

The Rules provide detailed procedures for handling cases transferred from the dissolved Intellectual Property Appellate Board (IPAB), along with new IP cases and appeals. The introduction of these specialized divisions aims to enhance the efficiency and expertise in adjudicating IP matters.

This development will complement the efforts of the Delhi and Madras High Courts, further streamlining IP jurisprudence across the country.

Patents

No Mediation, No Suit: Pre-Institution Mediation Mandatory for Non-Urgent Cases1

Novenco (plaintiff) accused Xero Energy (defendant) of infringing its patents and designs by manufacturing and selling axial fans without consent. Novenco sought interim relief under Order XXXIX, Rules 1 and 2 of the Civil Procedure Code, claiming irreparable loss from continued sales. The suit was filed in June 2024, following cease-and-desist notices in 2022 and confirmation of infringement by a technical expert in December 2023.

The defendants argued that Novenco bypassed the mandatory Pre-Institution Mediation under Section 12-A (1) of the Commercial Courts Act, 2015, required for cases without urgent interim relief. Said section requires that a suit, which does not contemplate any urgent interim relief shall not be instituted unless the plaintiff exhausts the remedy of Pre-Institution Mediation.

A Single Judge Bench of the High Court of Himachal Pradesh observed that the cause of action first arose in July/ August 2022 and was confirmed in December 2023, suggesting the plaintiff was uncertain about the infringement until then. It questioned why the plaintiff did not pursue mediation between December 2023 and June 2024 if no urgency existed.

The Court found no genuine urgency justifying the avoidance of mediation and ruled that the interim relief request was a tactic to circumvent the mandatory mediation process. As a result, the plaint was rejected for non-compliance with Section 12-A (1).

The judgment reaffirms the mandatory nature of Pre-Institution Mediation for commercial disputes, barring urgency, aligning with Supreme Court rulings (Patil Automation Pvt. Ltd. vs. Rakheja Engineers Pvt. Ltd. and Yamini Manohar vs. T.K.D. Keerthi).

Eco-Friendly Lamp Patent Denied: Court Reinforces Traditional Knowledge Protection!2

The appellants filed a patent application (No. 201721043812) for an eco-friendly lamp made of a composition including panchagavya (cow products) and herbal leaves.

The application was initially rejected by the Controller of Patents, inter alia, under Section 3(p) of the Patents Act, 1970 that precludes from patentability an invention which, in effect, is traditional knowledge or which is an aggregation or duplication of the known properties of traditionally known component or components.

The claims of the application included a lamp made with components such as cow dung, urine, ghee, butter, milk, curd, and leaves from neem, lemon, and peepal trees and a method of mixing these ingredients, moulding them under specific pressure (900-1100 psi) and temperature (80-100°C).

The Madras High Court observed that Section 3(p) provides defensive protection of traditional knowledge by excluding inventions which are “in effect” traditional knowledge from patent eligibility. The term “in effect” in the provision ensures that there is no circumvention of the prohibition by concealing the usage of traditionally known components or their properties in a claimed invention.

The Court upheld the Controller’s decision, agreeing that the lamp’s composition primarily relied on traditional knowledge. The use of cow products and herbal leaves was considered part of traditional knowledge in India, disqualifying it from patent protection.

Whether the combination of these products in specific proportions for the production of a lamp falls outside the scope of clause (p)?

The Court observed that the answer depends on whether known properties of these products have been aggregated in the claimed invention. It ruled that the invention lacked inventive step since working out specific proportions through experimentation is considered routine. The argument that the lamp was eco-friendly and carbon-neutral did not add inventiveness, as these properties were incidental to the known materials used. The appeal was dismissed, and the patent application was rejected.

Missing a Hearing Does Not Constitute Abandonment of Application3

Source: IAM Media, India: Patent Prosecution

Star Scientific filed a patent application in India based on an international Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) application. After receiving the First Examination Report (FER), the company submitted a response with amendments but failed to attend a scheduled hearing citing financial difficulty.

The Controller rejected the patent application citing that Star Scientific’s representatives did not attend the hearing and the objections raised in the FER were deemed unresolved, leading to the application’s refusal under Section 15 of the Patents Act, 1970.

The applicant submitted that a detailed response to the FER has already been filed and cited financial difficulty as the reason for missing the hearing and argued that this should not be construed as abandonment of the application. The company highlighted that the patent had been granted in nine other jurisdictions, indicating its merit.

The Court noted that the Controller’s decision lacked specific reasons and did not address the detailed submissions from the company’s response to the FER. The Court rejected the argument that non-attendance at the hearing implied abandonment, citing previous judgments requiring a conscious act to demonstrate intent to abandon. Under the Patent Rules, applicants have fifteen (15) days to submit written responses after a hearing, but the rejection order was issued within ten (10) days, violating this procedure. The rejection order was set aside, and the matter was remanded to the Controller for reconsideration.

The Court emphasized that even without attending a hearing, the applicant’s submissions must be considered, and decisions must be accompanied by detailed reasoning.

Patent Office Issues Key Clarification on Form-27: What You Need to Know

The Indian Patent Office has issued a much-needed clarification via Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) list on Form-27. The clarifications have been provided citing various scenarios as provided in the table below.

| Scenario | Filing of Form-27 (without extension) |

|---|---|

| In respect of patents granted before 2022-23 | In respect of a period of three financial years, i.e. FY 2023-24 to FY 2025-26. Window period – 1st April, 2026 to 30th September, 2026. |

| In respect of patents granted in 2022-23 | Window period – 1st April, 2026 to 30th September, 2026 |

| In respect of patents granted in or after 2023-24 | For patents granted in FY 2023-24, counting of a period of three years starts from FY 2024-25.

Window period – 1st April, 2027 to 30th September, 2027.

For patents granted in FY 2024-25, counting of three-year period starts from FY 2025-26. Window period – 1st April, 2028 to 30th September, 2028. |

| Patents expired in FY 2023-24 | Form-27 only for the remaining period, i.e. for FY 2023-24- Window period -1st April, 2024 to 30th September, 2024. |

| Patents expiring in the FY 2024-25 | Form-27 only for the remaining period, i.e. FY 2023-24 and 2024-25. Window period – 1st April, 2025 to 30th September, 2025 |

The deadline for filing Form-27 can be extended:

- by three months by filing Form 4 under Rule 131(2).

- further extended by six months under Rule 138.

- Where an extension of three months under Rule 131(2) is not availed, the deadline can be extended by six months under Rule 138.

However, if the patentee has failed to provide Form-27 details for the period of FY 2022-23 or earlier within the time limit prescribed under the earlier rules, Form 27 cannot be filed under the new rules for the lapsed FYs (FY 2021-22, FY 2022-23) by clubbing the lapsed period with the time period available for FY 2023-24 as a block of three years.

Geographical Indications

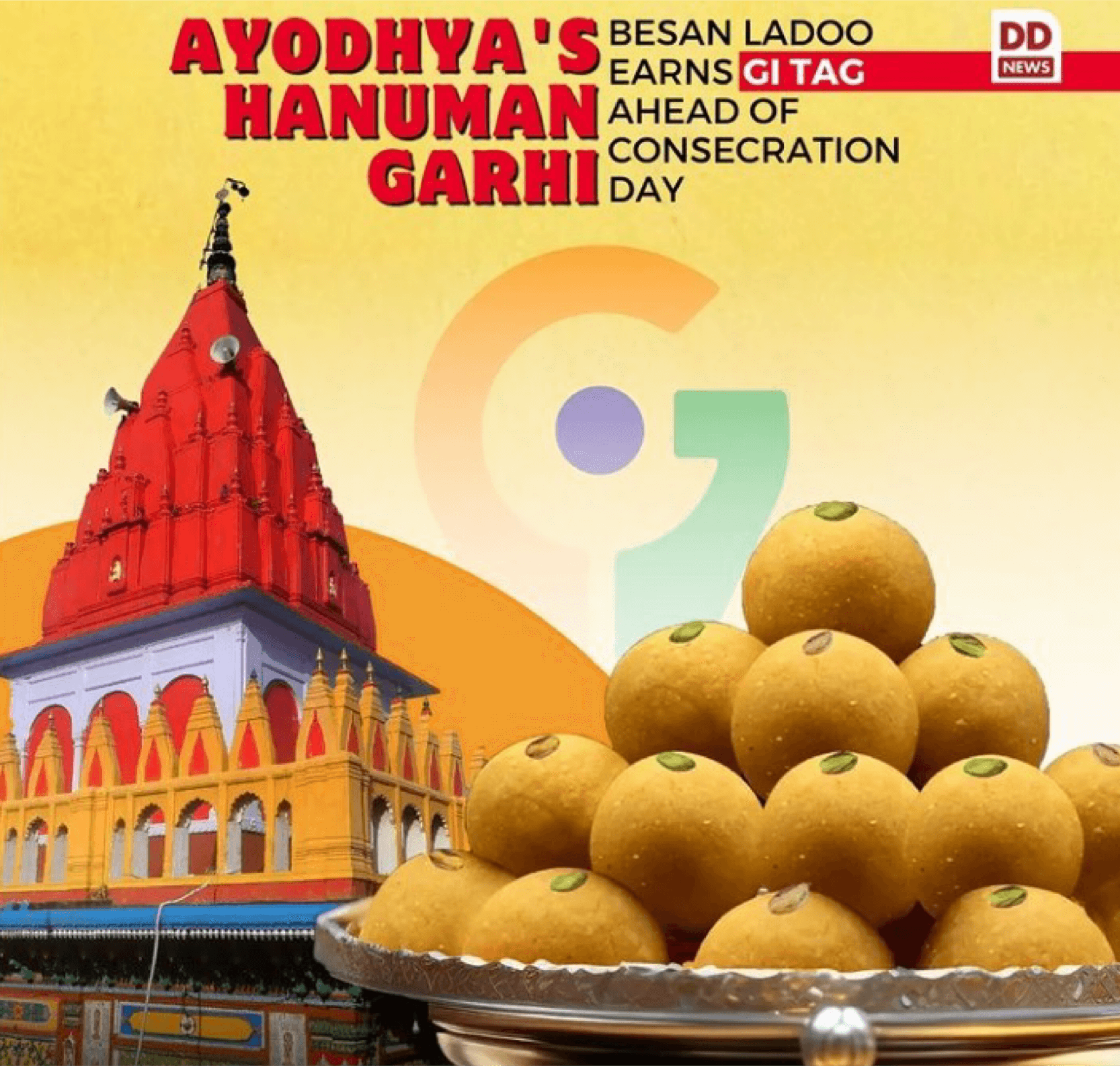

Ayodhya Bids for GI Tag: Celebrating Heritage with Hanumangarhi Laddu, Khurchan Peda, Khadau, Tika, and Gud

Ayodhya is seeking Geographical Indication (GI) tags for several of its traditional products, including the Hanumangarhi laddu, khurchan peda, khadau (wooden slippers), tika, and gud (jaggery). The GI Registry in Chennai has accepted the applications.

The laddu, khadau (traditional wooden sandals), and khurchan (a type of sweet) are integral to Ayodhya’s cultural heritage, and often associated with religious and festive occasions. The applications for a GI tag aim to protect the unique identity of these products, ensuring that only those produced in Ayodhya can use the names.

Securing a GI tag can enhance the marketability of these products, potentially boosting local economies by promoting tourism and local craftsmanship. The initiative also aims to preserve traditional methods of production that have been passed down through generations.

These efforts to secure GI tags are a step towards preserving Ayodhya’s rich cultural and culinary traditions, ensuring they are recognized and valued both nationally and internationally.

Trade Marks

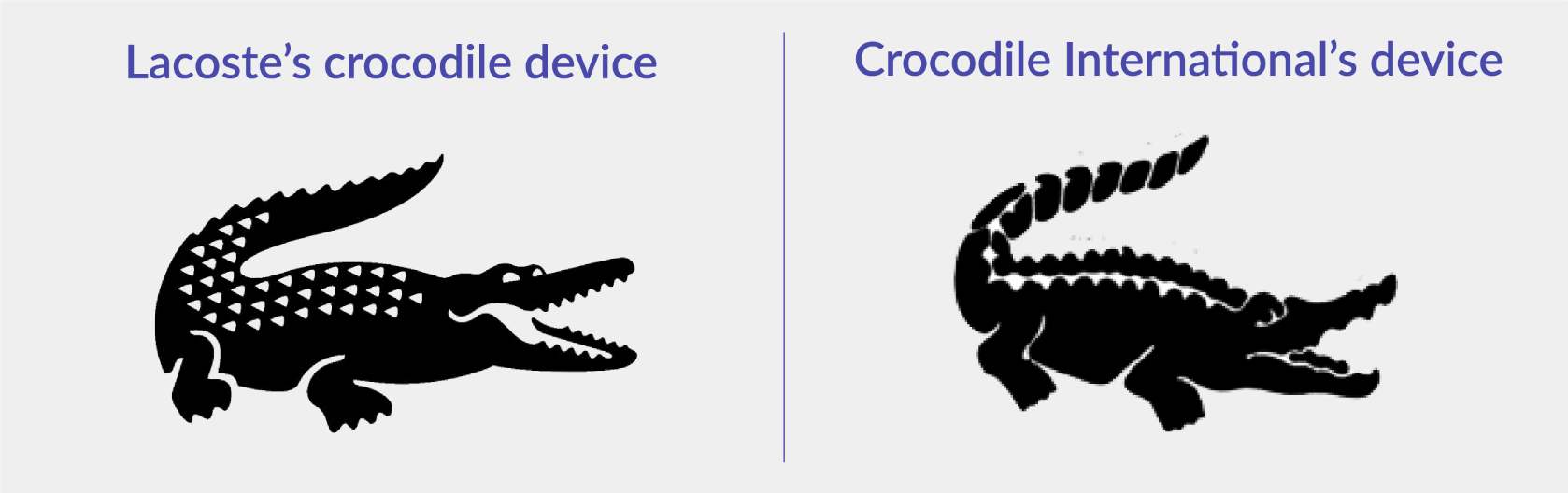

Lacoste vs. Crocodile International: A Case on Trade Mark Coexistence and Infringement in India4

In a recent judgment by the Delhi High Court, a long-standing trade mark dispute between Lacoste, the French clothing brand, and Crocodile International Pte Ltd. of Singapore reached a decisive conclusion. At the centre of this case was the use of the crocodile logo, a distinctive emblem associated with both brands, leading to claims of copyright and trade mark infringement in India.

The litigation was initiated by Lacoste and its Indian licensee, who sought an injunction to stop Crocodile International and its Indian partner from using a crocodile logo “ ![]() ” they alleged was deceptively similar to their own “

” they alleged was deceptively similar to their own “ ![]() ”.

”.

Lacoste asserted exclusive rights over its crocodile emblem, supported by trade mark and copyright registrations in India dating back to the early 1980s. In response, Crocodile International argued that it held prior rights to the Crocodile device ![]() in various markets since 1947, with Indian registrations for similar marks going back to the 1950s. Additionally, Crocodile International pointed to coexistence agreements signed with Lacoste in 1983 and 1985, arguing that these permitted both parties to operate under respective crocodile logos in designated regions, including parts of Asia.

in various markets since 1947, with Indian registrations for similar marks going back to the 1950s. Additionally, Crocodile International pointed to coexistence agreements signed with Lacoste in 1983 and 1985, arguing that these permitted both parties to operate under respective crocodile logos in designated regions, including parts of Asia.

The court addressed several critical issues, the foremost being the question of ownership and priority of use. After examining both parties’ registrations and claims, the court concluded that Lacoste’s standalone crocodile device, registered since 1983, granted it exclusive ownership and use in India. Although Crocodile International did possess older registrations, these pertained to composite marks “ ![]() ” that included both the crocodile device and the brand name “Crocodile,” rather than the standalone logo

” that included both the crocodile device and the brand name “Crocodile,” rather than the standalone logo ![]() contested in this suit. The court thus distinguished between Lacoste’s sole ownership of the crocodile device and Crocodile International’s rights to its composite mark.

contested in this suit. The court thus distinguished between Lacoste’s sole ownership of the crocodile device and Crocodile International’s rights to its composite mark.

Another significant aspect of the case was the similarity between the two trade marks. In assessing consumer perception, the court noted that both crocodile logos exhibited strong visual resemblances in terms of shape, posture, and orientation, which increased the risk of confusion. Minor differences, such as Lacoste’s crocodile facing right while Crocodile International’s faced left, were deemed insufficient to offset the dominant similarities. Given the average consumer’s imperfect recollection, the court determined that the overall resemblance between the logos could lead to “initial interest confusion,” where consumers might mistakenly associate Crocodile International’s products with Lacoste.

A key contention raised by Crocodile International was the applicability of the 1983 and 1985 coexistence agreements. Crocodile argued that these agreements provided mutual permission for both parties to use their respective crocodile marks in certain regions, including India.

However, after analysing the agreements, the court ruled that they did not authorize Crocodile International to use a standalone crocodile device without the accompanying brand name. The agreements were interpreted as granting Crocodile International rights only to its composite logo within India, affirming Lacoste’s exclusive rights over its standalone crocodile device.

In its final ruling, the Delhi High Court found in favor of Lacoste, affirming its rights to the crocodile logo in India and ordering an injunction against Crocodile International’s use of a deceptively similar logo.

This judgment reinforces the significance of clear, territorially bound provisions within coexistence agreements and highlights the potential for trade mark disputes when logos are similar enough to mislead consumers. The case underscores the court’s protective stance toward established brand identity and market recognition in the Indian context.

The Delhi High Court’s decision is a landmark case in the field of trade mark law, especially regarding coexistence agreements and brand identity in a competitive market. The ruling emphasizes the need for specificity in coexistence agreements, highlighting that territorial and usage rights should be unambiguously defined to prevent future disputes.

Furthermore, the court’s emphasis on consumer perception and “initial interest confusion” sets a strong precedent in cases where visual similarities between marks may create mis-associations, even if they are accompanied by minor differences.

This judgment not only upholds Lacoste’s rights to safeguard its brand but also serves as a reminder to brands with similar logos to exercise caution in new markets. By granting injunctive relief, the court reinforces the principle that brand identity is closely protected under Indian law, especially when such identity is based on longstanding consumer recognition and market presence.

Copyright

Bombay High Court Nixes Goa’s Wedding Music Exemption in Landmark Copyright Ruling5

An impactful judgment from the Bombay High Court at Goa has set aside a controversial circular issued by the State of Goa, marking a decisive win for copyright holders.

Phonographic Performance Ltd. (PPL), a major music rights organization, had filed a petition challenging the circular, which was issued on January 30, 2024 exempting marriage festivities and other social events from needing music licenses under specific copyright provisions.

The circular relied on Section 52(1) (za) of the Copyright Act, 1957, which allows music to be played at “bona fide religious ceremonies” and certain marriage-related festivities without infringing copyright. However, PPL argued that Goa’s circular interpreted this exemption too broadly, significantly impacting its rights to license music for public performances and collect royalties. The circular’s language extended the exemption to include “wedding/marriage events and other social festivities,” which PPL contended overstepped the statutory limits and undermined their ability to enforce copyright protections.

After reviewing the case, the High Court agreed with PPL, finding that the State’s circular went beyond simply informing the public about the law. The court held that by broadly exempting music performances at weddings and other social gatherings, the circular had infringed on PPL’s rights to control and license music performances—a right guaranteed by the Copyright Act. The Court clarified that only the judiciary, not an executive authority, could interpret the scope of exemptions under Section 52(1) (za).

This ruling reinforces the need for precision in interpreting copyright exemptions and upholds copyright owners’ rights to enforce licenses for public performances, even for marriage-related events, unless explicitly exempted by law.

For copyright societies and rights holders, the judgment is a reminder of the importance of safeguarding statutory protections and ensuring that copyright exemptions are not expanded beyond legislative intent.

Media Laws

Aashiqui in Court: A Legal Perspective6

In the latest chapter of Bollywood’s legal drama, the iconic Aashiqui film franchise found itself at the centre of a trade mark dispute.

In this case, the plaintiff, Vishesh Films Private Limited, the co-producer of the beloved original Aashiqui films, passionately defended their rights over the registered trade marks “Aashiqui” and “Aashiqui Ke Liye.” On the other side stood the defendant, Super Cassettes Industries Limited, which sought to launch their new project titled “Tu Hi Aashiqui.”

The crux of this legal saga lay in the battle for brand identity and the looming spectre of public confusion. The plaintiff argued that their established trade marks were the lifeblood of the Aashiqui brand, shielding it from further sequels or derivative works that could tarnish its legacy.

Meanwhile, the defendant, while acknowledging their joint ownership of the Aashiqui franchise, confidently claimed that their new title was distinct, aiming to break free from the shadow of its predecessors.

The Delhi High Court opined on the generic nature of the term “Aashiqui,” stating that, while it evokes themes of romance, it does not describe the film’s broader narratives. The Court concluded that “Aashiqui” is a distinctive mark that has garnered a strong reputation and goodwill over the years, making it eligible for trade mark protection.

Despite the defendant’s assurances that their film would not be a sequel, the Court found that the inclusion of “Aashiqui” in the title “Tu Hi Aashiqui” could mislead audiences into believing the film was connected to the original franchise. The defendant attempted to use a disclaimer stating that their film was not a sequel or derivative work of the Aashiqui films, but the Court deemed this insufficient to mitigate public confusion, given the deep-rooted association between the trade mark and the Aashiqui brand.

In addressing the principle of estoppel, the Court considered whether the plaintiff’s previous response to the Examination Report regarding the trade mark for “Aashiqui” would bind them in this dispute. The plaintiff had previously stated that their mark did not resemble the cited trade marks, a statement made to compare the visual and conceptual elements of the marks in question. The Court determined that this response did not amount to an admission that would prevent the plaintiff from asserting their trade mark rights in different contexts.

Moreover, the Court noted that the goods and services associated with the plaintiff’s trade mark, particularly under Class 41, did not overlap with those of the cited trade marks. As such, the plaintiff’s earlier response could not be interpreted as a waiver of their rights in this case. This ruling underscored the importance of context in trade mark disputes and affirmed the plaintiff’s ability to defend their brand without being constrained by prior statements.

As the Court weighed the implications of the plaintiff’s unilateral registration of the trade mark “Aashiqui” as a device mark and the defendant’s joint ownership of the film franchise, it noted that the plaintiff had adopted a conciliatory stance by offering to amend the trade mark registration to include the defendant as a co-proprietor. This gesture reflected the plaintiff’s willingness to collaborate in protecting the Aashiqui brand, allowing both parties to jointly oppose any potentially infringing trade marks, thereby preserving the integrity of the franchise.

As the legal drama unfolded, this case highlighted key themes of brand integrity and contractual obligations in the glamorous yet fierce world of Bollywood.

- Novenco Building & Industry A/S vs. Xero Energy Engineering Solutions Private Ltd. & Another. (2024:HHC:7518). https://shorturl.at/ML1SI

- M/s. The Zero Brand Zone Pvt. Ltd. And Others vs. The Controller of Patents & Designs (OA/32/2020/PT/CHN). https://shorturl.at/6SG3b

- Star Scientific Limited vs. The Controller of Patents and Designs, C.A. (COMM.IPD-PAT) 20/2024 [2024:DHC:5643]. https://rb.gy/iyzpfj

- Lacoste & Anr. vs. Crocodile International Pte Ltd & Anr. CS(COMM) 1550/2016. https://rb.gy/61bmr4

- Phonographic Performance Limited vs. State of Goa (Writ Petition No. 253 of 2024). https://tinyurl.com/yj9z37k4

- Vishesh Films Private Limited vs. Super Cassettes Industries Limited (CS (Comm) 68/2024). https://tinyurl.com/2eanbs24

Questions regarding the above developments

and their potential impact on your business?

Reach out to the client service team at ipconnect@walaw.in

To stay updated on our insights, subscribe here.

IPulse Editions

Second Edition | IPulse | A Quarterly IPR Update

- 20 August 2024

If you would like a copy of the newsletter, reach us at ipconnect@walaw.in.

First Edition | IPulse | A Quarterly IPR Update

- 01 June 2024

The Indian Patent Office granted over one lakh patents in the year from 15-Mar-2023 to 14-Mar-2024 which amounts to 250 patents every working day. A record number of 1532 patent orders were issued in a single day!

If you would like a copy of the newsletter, reach us at ipconnect@walaw.in.