Patents

Madras High Court Clears Path for Animal-Based Antibody Patents

A recent case1 before the Madras High Court involved the issue of patentability of an invention pertaining to a process for generating antibodies in non-human mammals. The Controller of Patents rejected the application under Section 3(i) of the Patents Act, which excludes methods related to diagnosis and treatment. Specifically, the Controller argued that the invention involves a process for producing antibodies in non-human mammals by immunizing them with a desired antigen, a method that, according to the Controller, falls under the scope of Section 3(I).

On appeal, the Court analysed the provisions of Section 3(i) observing that the section distinguishes between human and animal treatment, the first limb of the section applies to the treatment of human beings, while the second limb focuses on the treatment of animals. The Court noted that the disjunctive “or” clearly separates these two limbs, establishing that the second part specifically governs processes related to animals.

The Court then examined the three specific purposes outlined in Section 3(i) for treating animals: (i) to render them free from disease, (ii) to increase their economic value, and (iii) to increase the economic value of their products. While the first purpose—treating animals to make them free from disease—could arguably apply to human beings, the Court concluded that the use of the word “them” in reference to animals meant that this purpose in the second limb applied only to animals.

The Court observed that the invention did not aim to treat the mice to make them free from disease, nor did it seek to increase their economic value, or the value of any products directly derived from the animals. In this case, the process involved creating genetically modified mice that produced non-murine antibodies, but these antibodies were not considered products of the animals in the same sense that other animal products (such as meat, milk, or fur) are.

Therefore, the Court concluded that the antibodies produced in the invention cannot be considered products of the mice and that the claimed method does not fall under the scope of Section 3(i).

Post-Grant Patent Challenge: Petitioner Bears the Burden of Proving Revocation

In a recent judgment², the Madras High Court dismissed a petition challenging the validity of a patent granted for a method of preparing chiral beta-amino alcohols.

The Court held that in cases of post-grant challenge, the burden is only on the Petitioner to establish that the grant requires to be revoked for not being novel or not showing any inventive step. The Court observed that the invention has to be considered as whole and dissecting the invention into parts and finding individual parts to be obvious to hold that the invention itself is obvious, is not the right approach to be adopted. The court stated that the patent had been granted after rigorous examination by the Patent Controller, and that no substantive grounds were presented to justify revocation.

The Court held that merely because, the Petitioner, being a competitor is entitled as a ‘person interested’ to challenge the patent, post grant, the said right is not automatic and unless the Petitioner establishes strong grounds for revocation by citing relevant prior arts and also show how the subject patent is not novel and that it lacks inventive step or does not show any technical advance, the Petitioner is not entitled to succeed.

The Court also shed light on the definition of the term ‘person interested’ as required under Section 64 of the Patents Act for challenging the validity of a patent. The Court observed that the definition is not static and even if a person may not be a ‘person interested’ when the grant of the patent concerned was published and yet on account of his activities at a later point of time, he may assume the character or disposition of a ‘person interested’. The definition of ‘person interested’ employed in Section 2(1)(t) of the Patents Act does not require that the person interested should be only in manufacturing in the same field. The ‘person interested’ is an inclusive definition and merely because the Petitioner is not a manufacturer, he cannot be shut out from filing an application for revocation.

India’s Remarkable Growth in the Global Intellectual Property Landscape —

The World Intellectual Property Indicators (WIPI) Report 2024

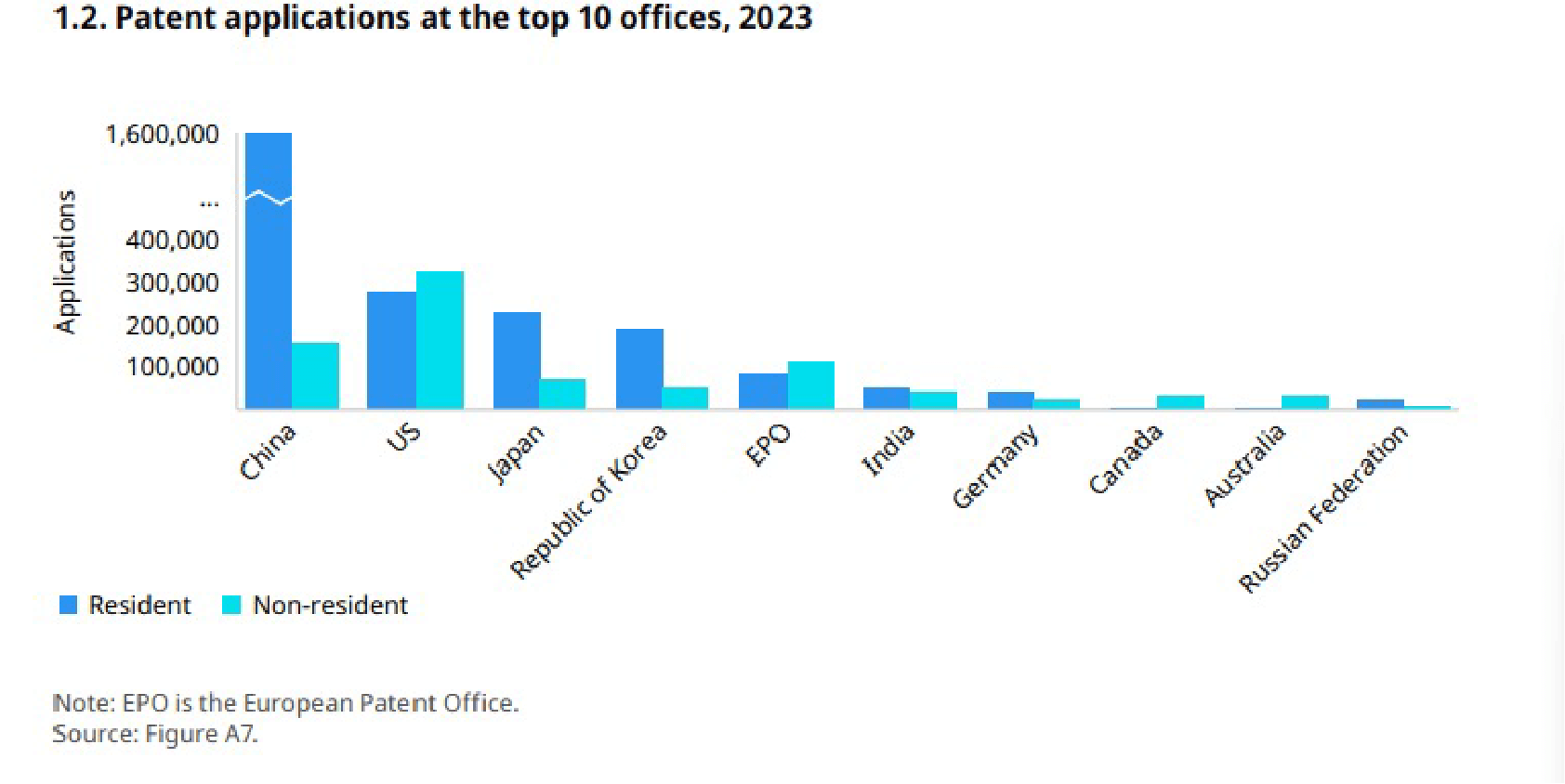

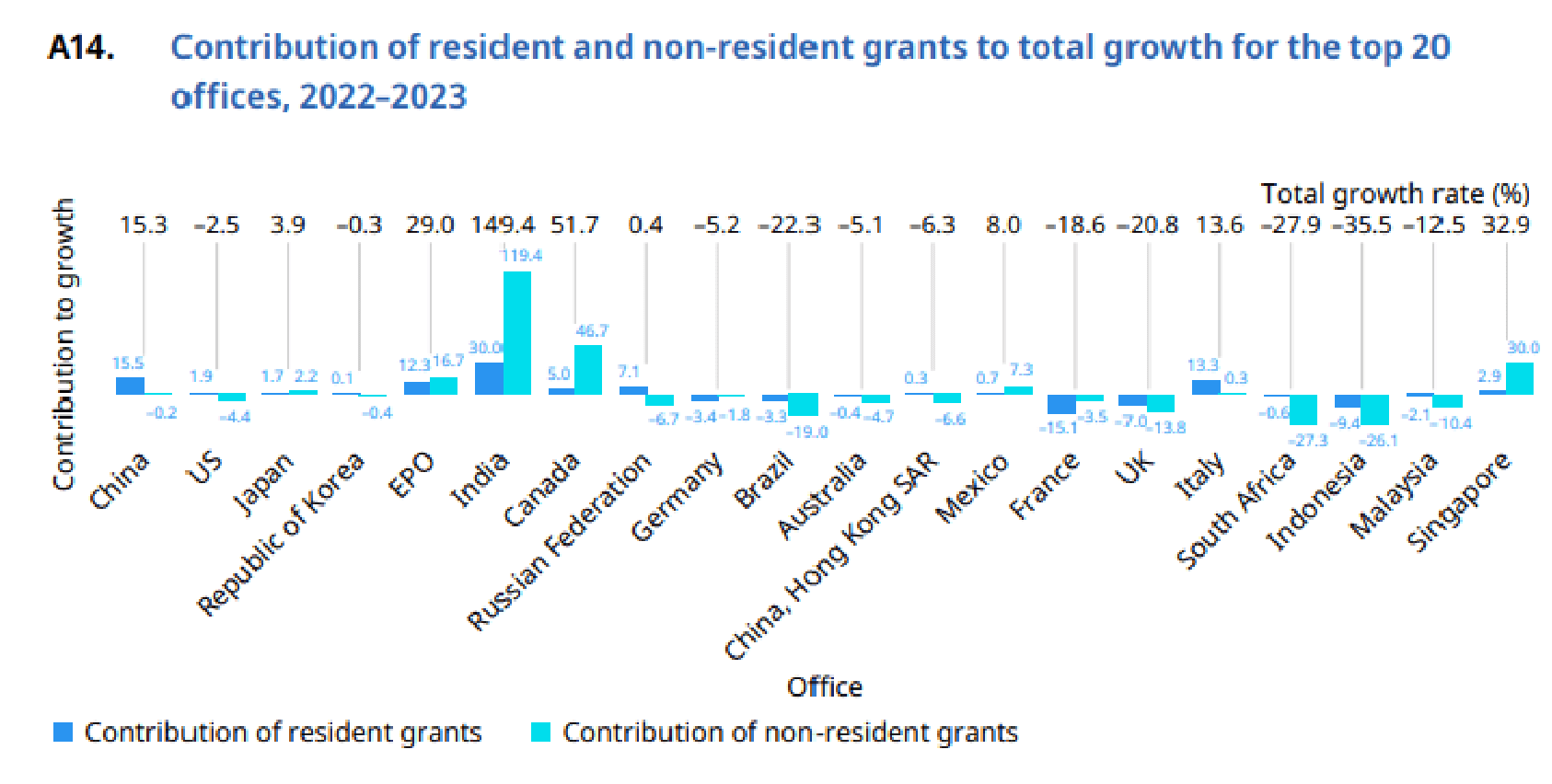

According to the WIPI Report³, the annual survey of intellectual property (IP) activity around the world carried out by WIPO, India has made remarkable strides in the global IP landscape, ranking among the top 10 countries for patents, trademarks, and industrial designs.

India now stands 6th globally with 64,480 patent applications, marking a significant achievement as more than half (55.2%) of these applications came from domestic applicants, a first for the country.

Patent grants in 2023 saw an impressive 149.4% increase compared to the previous year. The industrial design sector also witnessed substantial growth, with applications rising by 36.4%, while trademark filings increased by 6.1%. India ranks fourth worldwide in trademarks, with nearly 90% of these filings originating from domestic businesses.

Notably, the Trademark Office of India now holds the second-largest number of active trademark registrations globally, with more than 3.2 million trademarks in effect. Between 2018 and 2023, patent and industrial design applications more than doubled, and trademark filings surged by 60%, underscoring India’s rapid growth in the IP domain.

Insights from the Comviva Technologies Ruling on Business Method Patentability

Patentability statutes vary across jurisdictions. In India, the Patents Act, 1970 [‘the Act’], establishes the criteria for patentability while detailing specific exclusions. Given the rapid advancements in computer-related technologies, particularly in the fintech domain, understanding legislative exclusions becomes imperative. Section 3(k) of the Act excludes mathematical or business methods, computer programs per se, and algorithms from patentability. The Manual of Patent Office Practice further describes “business methods” as encompassing activities related to the transaction of goods or services within commercial enterprises. This provision remains a contentious area, particularly in light of increasing software-driven innovations.

A recent case in the Delhi High Court dealt with this issue when Comviva Technologies Limited appealed against the rejection of their patent application for “Methods and Devices for Authentication of an Electronic Payment Card using Electronic Token.” The Assistant Controller of Patents and Designs had denied the application, citing Section 3(k) on the grounds that it pertained to a “business method” and a “computer program per se.”

The invention addressed the authentication of contactless cards using electronic tokens. Comviva argued that the invention provided a technical solution aimed at secure authentication, distinct from the actual financial transaction. In contrast, the Respondent maintained that the invention facilitated secure financial transactions and therefore fell within the scope of “business methods” as outlined in the Guidelines for Examination of Computer-Related Inventions (CRIs).

The Court emphasized that applications involving technical processes or apparatus must be analysed holistically. It noted that terms such as “business” or “payment” alone do not necessarily categorize an invention as a business method. Referring to key precedents, including Ferid Allani v. Union of India and Opentv INC v. The Controller of Patents and Designs, the Court highlighted the need to examine whether the invention delivers a technical effect or advancement.

In its judgment, the Court observed that the invention addressed the technical problem of unauthorized transactions by employing secure tokens with limited validity. It concluded that the invention did not fall under the exclusions of Section 3(k), as it represented a technical advancement distinct from the financial transaction itself. Accordingly, the rejection of the patent application was overturned, and the appeal was upheld.

This decision reinforces the significance of differentiating technical solutions from business concepts in determining patentability under Section 3(k).

It reflects a progressive approach towards encouraging computer-related innovations, which play a vital role in building a technology-driven society.

Biological Diversity Rules, 2024 – Simplifying procedures for conserving biological diversity in India

The Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India, notified the Biological Diversity Rules, 2024 (“Rules”), which have now come into effect from December 22, 2024. These Rules supersede the previous regulations established in 2004 and are in furtherance to the Biological Diversity (Amendment) Act, 2023 that came into force from April 01, 2024. The Rules are aimed at enhancing the management and conservation of biological diversity in India and include specific provisions regarding Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) related to biological resources.

The Rules provide for a three-tier governance structure, simplified forms, online procedures including payments with defined timelines, updated fee structure, provisions for regularizing past violations/non-compliances prior to the Amendments coming into force, and clear penalties.

Key provisions related to IPR include prior approval requirement for both Indian and Foreign entities before applying for IPR, registration for Indian Entities, obligation to notify once IPR is granted, obligations for using foreign biological resources within India, obligations for using Indian biological resource for non-commercial research outside India.

The Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India, notified the Biological Diversity Rules, 2024 (“Rules”), which have now come into effect from December 22, 2024. These Rules supersede the previous regulations established in 2004 and are in furtherance to the Biological Diversity (Amendment) Act, 2023 that came into force from April 01, 2024. The Rules are aimed at enhancing the management and conservation of biological diversity in India and include specific provisions regarding Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) related to biological resources.

The Rules provide for a three-tier governance structure, simplified forms, online procedures including payments with defined timelines, updated fee structure, provisions for regularizing past violations/non-compliances prior to the Amendments coming into force, and clear penalties.

Key provisions related to IPR include prior approval requirement for both Indian and Foreign entities before applying for IPR, registration for Indian Entities, obligation to notify once IPR is granted, obligations for using foreign biological resources within India, obligations for using Indian biological resource for non-commercial research outside India.

These provisions aim to protect India’s biodiversity while facilitating responsible innovation and equitable sharing of benefits arising from its use.

Copyright

Dhanush vs Nayanthara Legal Battle Heats Up Over ‘Naanum Rowdy Dhaan’ Clip

The ongoing legal battle between Tamil actors Dhanush and Nayanthara has attracted considerable attention within the entertainment sector. The dispute revolves around the inclusion of footage from the 2015 film Naanum Rowdy Dhaan in Nayanthara’s Netflix documentary, Nayanthara: Beyond the Fairytale. Dhanush’s production company has initiated a lawsuit against Nayanthara, her director husband Vignesh Shivan, and Netflix for copyright infringement.

Notably, the documentary, which runs for one and a half hours, features nearly 10 seconds of this footage. A key defence that Nayanthara may invoke is the de minimis defence in copyright law. The term “de minimis” is a legal maxim commonly used to privilege trivial legal violation.

This defence is rooted in case law rather than the Copyright Act itself. In a landmark case4, the Delhi High Court held that de minimis doctrine would be applicable for copyright cases as the fair use concept would be a bad theoretical fit for trivial violations, de minimis analysis is much easier and a de minimis determination, is the least time consuming and in the interest of the parties as also the society that litigation reaches its destination in the shortest possible time. The Court elucidated five factors for determining minimum use (i) the size and type of the harm, (ii) the cost of adjudication, (iii) the purpose of the violated legal obligation, (iv) the effect on the legal rights of third parties, and (v) the intent of the wrongdoer.

In the context of performers, the Court held that if a performer is to give a chat show or an interview, surely “Einstein’s Theory of Relativity” or the discovery of the “Boson Particle” would not be the subject matter of discussion. The life and the achievement of the performer would be discussed. The life of the performer and her performances cannot be separated and if in the natural setting of a chat show she were to sing more than a wee bit, but not substantially the full songs, as long as the singing duration is limited to a minute or so at a time, it would be a case of de minimis use.

Screenwriters Rights Association of India Officially Recognized as a Copyright Society

The Screenwriters Rights Association of India (SRAI) has reached a significant milestone with its official recognition as a copyright society under Section 33 of the Copyright Act, 1957.

This recognition enables SRAI to manage and administer copyrights for dramatic and literary works across India.

A copyright society in India is an organization that is authorized by the government to manage and administer the rights of copyright holders, particularly in relation to the collective licensing and collection of royalties for the use of copyrighted works. Copyright societies represent the interests of creators, such as authors, musicians, filmmakers, and other content creators, ensuring they receive fair compensation for the use of their works.

With this new status, SRAI is now authorized to collect royalties on behalf of screenwriters, ensuring they receive fair compensation for the use of their works. This includes royalties for derivative works like sequels, adaptations, and spin-offs, as well as content shared on digital and social media platforms. The recognition also strengthens the enforcement of screenwriters’ moral rights, ensuring proper attribution and protecting against unauthorized alterations of scripts.

Trademarks

When Domains Collide: The JioHotstar Legal Battle and Cybersquatting

The JioHotstar domain controversy began when a Delhi-based app developer registered the domain name JioHotstar.com in early 2023, anticipating a merger between JioCinema and Disney+ Hotstar. The developer later sought to sell the domain to Reliance Industries in exchange for funding his higher education abroad. However, Reliance rejected the offer and threatened legal action, leading the developer to sell the domain to two siblings in Dubai.

This case has drawn attention to the practice of cybersquatting which refers to the practice of registering, using, or trafficking in domain names that are identical or confusingly similar to the trademarks or brand names of well-known companies, organizations, or individuals, with the intention of profiting from the established reputation or traffic associated with those names. This often involves buying domain names that are likely to attract visitors who mistype or confuse them with popular websites, and then selling those domain names at a higher price to the rightful trademark holders or others interested in acquiring them.

Cybersquatting is usually considered both a form of cybercrime and trademark infringement, involving bad faith attempts to exploit a recognizable brand or redirect online traffic. The JioHotstar incident has raised concerns about the adequacy of existing laws in India, as there is no specific legislation addressing cybersquatting, and it falls under the broader provisions of the Trade Marks Act.

As the digital landscape continues to evolve, understanding the risks and legal implications of domain registration and use is increasingly important for businesses and individuals alike.

Monster’s ‘Energy for the Journey’ Missed the Mark

In a recent case5, an appeal was filed challenging the refusal of the Monster Energy Company’s trademark application for “ENERGY FOR THE JOURNEY.” The Trade Mark registry had rejected the application, citing that the mark was devoid of any distinctive character. The registry argued that the phrase was too generic and commonly used, making it incapable of distinguishing the appellant’s goods from those of others.

The Company’s counsel highlighted several other trademark registrations held by the company, but none of these were similar to the contested mark. The court upheld the Trade Mark registry’s decision, agreeing that “ENERGY FOR THE JOURNEY” was too common and descriptive to function as a trademark unless it acquired a secondary meaning through extensive use and recognition in the market.

The court emphasized that the subject marks is too common to be monopolized by any individual. The subject mark are generic words used by many other people. It is well settled law that common language words or descriptive words or common words and names or single colour cannot be trademarked by any trader unless and until such trade names have acquired such a great reputation and goodwill in the market that the common language word has attained a secondary significance.

In conclusion, the court dismissed the appeal, reaffirming the decision to reject the trademark registration. However, the appellant was granted the opportunity to reapply for the same trademark in the future if the Company is able to establish that by the long usage of the said Trade Mark, it has become distinctive.

Designs

Riyadh Design Law Treaty – A significant milestone in International Intellectual Property Law

The Design Law Treaty (“the treaty”), also known as the Riyadh Design Law Treaty, was officially adopted on November 22, 2024, by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

The treaty aims to harmonize and streamline the procedural aspects of design laws among WIPO member states, thereby facilitating a more coherent and efficient framework for the protection of industrial designs on a global scale.

The treaty introduces a unified legal framework designed to simplify the registration process for industrial designs internationally. Key provisions of the treaty include standardized application requirements, a 12-month grace period for disclosing designs prior to filing, provisions enabling applicants to delay publication of their designs for up to six months post-filing, allowance for multiple designs in a single application while preserving the original filing date, more flexible time extensions for applicants who miss critical filing deadlines, and encouragement of electronic submissions and exchange of priority documents. These provisions are anticipated to significantly alleviate bureaucratic hurdles, enhance accessibility for designers, and stimulate innovation across various industries. The treaty is particularly beneficial for start-ups, individual designers, and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), promoting innovation and simplifying access to global markets.

In India, design registrations have seen a remarkable increase, with domestic filings rising by 120% over the past two years and overall design applications growing by 25% last year.

This surge underscores the importance of having robust intellectual property frameworks. The treaty represents a pivotal advancement in strengthening India’s intellectual property landscape concerning design protection. While some provisions of the treaty, such as the grace period and options for delaying publication, are not currently included in India’s existing Design Law, it is expected that India will adapt its regulations to align with the treaty’s non-binding nature facilitating a more conducive environment for protecting industrial designs while fostering compliance with international standards.

The adoption of the treaty marks a significant milestone in international intellectual property law. As countries begin to ratify this treaty, it is poised to reshape the landscape of design protection worldwide. By establishing a more predictable and accessible system for designers, the treaty not only enhances legal certainty but also encourages creativity and economic growth across diverse sectors.

Artificial Intelligence

AI vs. Copyright: The Battle Reaches Indian Courts

Asian News International (ANI) has filed a lawsuit against OpenAI in the Delhi High Court for alleged copyright infringement in training ChatGPT using copyrighted news content without authorization. Open AI and numerous other generative AI companies are also facing multiple copyright suits in the United States, including one from the New York Times against OpenAI for using its articles to train the ChatGPT model.

Indian copyright law offers flexibility through the “fair dealing” doctrine, akin to the U.S. “fair use” principle. This allows for the use of copyrighted material under specific conditions, with factors such as purpose, extent of use, and potential market competition playing a role in determining fair dealing. The goal is to strike a balance between the rights of creators and public access to information.

Generative AI models, such as Large Language Models (LLMs), are trained on enormous datasets, often containing millions of documents. This raise concerns over the logistical challenges of securing licenses and the possibility of hindering competition, as only well-funded companies may be able to obtain such licenses. Obtaining license from every copyright owner would be a tremendous compliance burden and may stifle the growth of a revolutionary technology. Meanwhile, copyright holders argue that their works possess both economic and moral value. Unauthorized use of their content not only deprives them of potential earnings but also risks misrepresentation. This could discourage creators from sharing their work, fearing exploitation without fair compensation.

The growing wave of copyright lawsuits against generative AI companies highlights the tension between technological innovation and IP rights.

The debate underscores the need for a balanced approach that fosters innovation without undermining the economic and moral interests of copyright holders. Addressing these concerns will require thoughtful legal frameworks.

- Kymab Limited vs. Assistant Controller of Patents & Designs. (2024: MHC:3498). https://bit.ly/3PGFPq3

- Embio Limited vs. Malladi Drugs & Pharmaceuticals Ltd. (ORA/35/2014/PT/CHN). https://bit.ly/3WoV4Yu

- World Intellectual Property Indicators Report 2024, WIPO. https://shorturl.at/peaLY

- India TV Independent News Service Pvt. Ltd. vs. Yashraj Films Pvt. Ltd., 21 August 2012. (FAO(OS) 583-584/2011). https://bit.ly/42ktlfx

- Monster Energy Company vs. The Registrar of Trade Marks, 19 November 2024. (CMA (TM) No.7 of 2024) (Madras High Court). https://bit.ly/40IAPb2

Questions regarding the above developments

and their potential impact on your business?

Reach out to the client service team at ipconnect@walaw.in

To stay updated on our insights, subscribe here.

IPulse Editions

Third Edition | IPulse | A Quarterly IPR Update

- 13 November 2024

The provisions of the Jan Vishwas (Amendment of Provisions) Act, 2023 (“Act”) pertaining to Intellectual Property have come into force starting August 1, 2024, pursuant to the notification by the DPIT.

If you would like a copy of the newsletter, reach us at ipconnect@walaw.in.

Second Edition | IPulse | A Quarterly IPR Update

- 20 August 2024

If you would like a copy of the newsletter, reach us at ipconnect@walaw.in.

First Edition | IPulse | A Quarterly IPR Update

- 01 June 2024

The Indian Patent Office granted over one lakh patents in the year from 15-Mar-2023 to 14-Mar-2024 which amounts to 250 patents every working day. A record number of 1532 patent orders were issued in a single day!

If you would like a copy of the newsletter, reach us at ipconnect@walaw.in.